If you’re new to DynamoDB, or NoSQL in general, you’ll want to take some time to understand how access patterns drive how you model your data. If you’ve seen any of a number of the great re:Invent sessions by Rick Houlihan over the years you already understand it, at least enough to know that you need to think about it. If you haven’t, look them up on YouTube. They are insightful and often mind blowing.

Most conversations about using DynamoDB start with just that, access patterns. If you’re starting a new project and plan to use DynamoDB you’ll want to do your best to understand how you will need to access the data.

At some point, however, reality may set in, and you’ll remember that you are working on a highly agile team, with ever changing requirements as you learn what your customers’ needs are, and you pivot to meet those needs. Then what? What happens when the access patterns you initially thought were correct turn out to be missing something? This thought is often an argument for sticking with an SQL database, or it can lead to poor performing solutions to force the new access pattern to work within the current model. There is a better option!

Realtime Data Migration

Data migrations aren’t new; Amazon even has an entire service for it, Amazon Database Migration Service. They are, however, often quite scary. Most often they come with some amount of downtime (no one wants to hear that) and require significant configuration. More importantly, for us, Amazon DMS doesn’t support DynamoDB as a source (I know, crazy).

Fortunately, DynamoDB does have this really cool feature called Streams.

A DynamoDB stream is an ordered flow of information about changes to items in a DynamoDB table. When you enable a stream on a table, DynamoDB captures information about every modification to data items in the table.

Streams allow for a lot of really cool use cases, including transforming and copying data in near real time.

I recommend reading the Tutorial: Process New Items with DynamoDB Streams and Lambda to see some of the details on how it works, specifically with Lambda. We’ll talk about some of the key points below as it relates to our use case.

Let’s Dig In

To get started we’ll assume you have a table in place that holds your current data (we’ll refer to this table as the source table), and that you’ve figured out what new access patterns you need to support, along with what the data needs to look like to support it.

For our example we’ll assume the table has a partition key called PartitionKey and a sort key called SortKey.

The only change you need to make to the source table is to turn on Streams, if you haven’t already. Be sure to set the stream view type to new and old images. You can do this in the console from the DynamoDB table’s overview tab.

Next you’ll need a new table that supports your new access pattern; we’ll refer to this as the destination table. Be sure you have your new table provisioned to handle the throughput you’ll need. In most cases the write capacity can be set to the same as the source table. You’re not really going to be doing any reads from this table right now, so you can set that much lower, but don’t forget to adjust it when you start to read from it.

On this new table we have a bit more knowledge of DynamoDB, so we know that shorter attribute names save money, and therefore the new partition and sort keys will be pk and sk. We’ll also being adding a GSI, with keys gsi1_pk and gsi1_sk.

Next you’ll need a Lambda to process the stream data. We’ll use a utility package I created to assist with this, so the code for your lambda looks like this:

import AWS from 'aws-sdk';

import { AttributeValue, DynamoDBStreamEvent } from 'aws-lambda';

import { Migrator } from 'dynamodb-data-migration-migrator';

const migrator = new Migrator(

new AWS.DynamoDB(),

'destination',

converter,

['pk', 'sk']

);

export const handler = async (event: DynamoDBStreamEvent) => {

console.log(JSON.stringify(event));

await migrator.handleEvent(event);

}

function converter(image: { [key: string]: AttributeValue }): { [key: string]: AttributeValue } {

const converted = {

...image,

pk: image.PartitionKey,

sk: image.SortKey,

gsi1_pk: image.SortKey,

gsi1_sk: {

S: `new-${image.someKey.S}`

}

};

// @ts-ignore

delete converted.PartitionKey;

// @ts-ignore

delete converted.SortKey;

return converted;

}

In the code above you’ll see that we have a converter function that transforms an image (DynamoDB terminology, I hate it) from the source table into what is needed in the destination table. You can see that we are putting the old SortKey value in the gsi1_pk and adding a computed value as the value for gsi1_sk. We’re also renaming our keys while we’re at it.

Under the covers there are some important things happening that we should go over.

Record Types

There are three types of records you can receive in the stream data, INSERT, MODIFY and REMOVE. These records are just what they sound like (why they couldn’t use industry standard insert/update/delete, or even create/update/delete is beyond me). What’s cool about these records is that they contain the entire view of the change. In the case of an insert it’s the entire new record. For a delete it includes the record as it was before it was deleted. For updates you get both the record as it was before the update as well as after. This allows for some powerful functionality. For us it means we have everything we need to know what to do in the destination table.

Deletes

We’ll start with one of the easier records to manage. When a delete occurs in the source table you need to also delete the record from the destination table. Figuring out what record to delete is pretty simple. First, you transform your deleted item into its new form and get the key attributes from the converted item. The keys are all you need to delete the record in the destination table. Once you have the key you just call DeleteItem on the new table with that key.

Inserts

Inserts are almost as easy as deletes, and in some ways maybe easier. When an insert occurs in the source table you need to insert that record into the destination table. To do this you just transform the new item and do a PutItem with the transformed item. If you are changing your data structure so that a single item from the source table results in multiple items in the destination table (a common advanced pattern) you’ll have to do a PutItem for each new item. It’s tempting to think that you should use transactions here, and there may be some exceptional cases where you should, but most often you can safely use batch writes. The worst that will happen is a batch fails, leading you to have to reprocess it. In that case you may have a record that is partially migrated. Keep that in mind as you start to use the new data. It’s likely something you’d need to be aware of after the migration process as well.

Note: the utility package current only supports one to one mappings and does not support transactions.

Updates

Updates can be a bit more complicated. In their simplest form they are just like an insert, and if you aren’t changing the data in the primary key you can ignore the other cases. If, however, you are changing the data in primary key, you potentially have more work to do. An update will include both the before and after version of the source item. You’ll want to convert both of these items to the new form. Then you need to compare the keys of the before and after items. If the keys match you just need to do a PutItem with the after item. If the keys don’t match you also need to do a DeleteItem for the key of the before item. This is a place where your use case may require transactions. If you can’t tolerate both the old and new versions being present for a short period of time, and also can’t tolerate the record being gone for a period of time, you’ll need to do the PutItem and DeleteItem in a transaction. Most often you probably don’t care too much, keeping in mind that it won’t be inconsistent for very long.

Now What?

We now have a lambda that is transforming every change to our source table and replicating it to the destination table. That’s great for everything going forward, but if you only cared about going forward you wouldn’t bother with this process. You need to get all the records from the source table into the destination table. To do this we’ll create a Step Function that will scan your source table and perform an UpdateItem on each record. This update will trigger the stream process. We don’t really want to change the data, but this is NoSQL, so we can just add an indicator that we’ve touched the record that we can ignore.

Tip: to keep this value out of the new table you just need to remove it from the converted item.

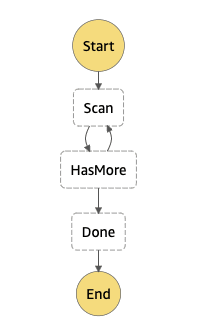

The step function is pretty simple; it has the following steps:

- A lambda invoke to scan the table, and do the updates. The step will pass in the data from the previous run so that the

LastEvaluatedKeycan be used to start the paging. - A choice step looks at the output from the function and if there is a value in

LastEvaluatedKeyit calls the lambda function again, passing in that value.

The function will page through the data until it runs low on time. When it does it returns the LastEvaluatedKey. There is no batch option for UpdateItem, but you can make multiple calls using threads in most languages.

A few notes here. First, this can put a significant load on your table source table (and result in a load on the destination table), so be sure to make sure you have the capacity adjusted accordingly. Second, if you need to control the volume of parallel updates you can add a limit to the scan. Third, if you want to increase the performance you can take advantage of Parallel Scans (https://docs.aws.amazon.com/amazondynamodb/latest/developerguide/Scan.html#Scan.ParallelScan). To do this you can either include the segment information when you invoke the step function, and invoke it multiple times, or you can add a map state around the entire process above, with each mapped state passing in the segment information for that set. Be careful, this can quickly overwhelm your capacity if you parallelize too much.

Here is the lambda code for our example:

import AWS from 'aws-sdk';

import { Context } from 'aws-lambda';

import { Key } from 'aws-sdk/clients/dynamodb';

const dynamodb = new AWS.DynamoDB.DocumentClient();

export const handler = async (event: any, context: Context) => {

console.log(JSON.stringify(event));

let lastEvaluatedKey: Key = event?.input?.Payload?.LastEvaluatedKey;

do {

const response = await dynamodb.scan({

TableName: 'source',

Limit: 25,

ExclusiveStartKey: lastEvaluatedKey,

ProjectionExpression: 'PartitionKey,SortKey'

}).promise();

const promises: Promise<AWS.DynamoDB.DocumentClient.UpdateItemOutput>[] = [];

for (const item of response.Items) {

promises.push(dynamodb.update({

Key: item,

TableName: 'source',

ConditionExpression: 'attribute_exists(#pk)',

ExpressionAttributeNames: {

'#pk': 'PartitionKey',

'#migrated': '_migrated'

},

ExpressionAttributeValues: {

':now': new Date().toISOString()

},

UpdateExpression: 'SET #migrated = :now'

}).promise());

}

await Promise.all(promises);

lastEvaluatedKey = response.LastEvaluatedKey;

} while (lastEvaluatedKey && context.getRemainingTimeInMillis() > 30000);

return {

LastEvaluatedKey: lastEvaluatedKey

};

}

Notice that we are checking the context.getRemainintTimeInMillis() on each loop. This will allow us to exit if we have less that 30 seconds remaining, which should be enough time to run a batch.

The state machine looks like this:

Note: in a real world setting you should add some retry and error handling to the state machine. This one has been kept simple to show the primary components.

Cost Of course, all of this costs money, so how much? The answer depends on how much data you need to migrate, but probably not as much as you might think. Let’s look at an example.

Assuming the following:

4KB avg record size

10,000,000 records in the table

100,000 daily record updates

60 days before you can transition to the new table

Writes to the destination table

10,000,000 existing record writes

100,000 daily record updates x 60 days = 6,000,000 total writes

Combined total writes to the destination table = 16,000,000

16,000,000 x 4 (1 WCU is 1KB) = 64,000,000 WCU

Total cost: $80

Migrator Lambda

~ 100,000 invocations for existing records (batches of 100)

Avg. duration ≈ 1000ms ≈ $1

~ 1,200,000 invocations for updates (5 record avg. batch)

Avg. duration ≈ 100ms ≈ $1.25

Total cost: $2.25

Scanner step function

~ 1,000 state transitions (assuming 10,000 records

processed before hitting timeouts in lambda) ≈ $.03

(free if you are below the 4,000 free each month)

Total cost: $.03

Scanner Lambda

~ 1,000 invocations running at 15 minutes ≈ $7.50

Total cost: $7.50

Reads from source

10,000,000 = $1.30

Total cost: $1.30

Writes to source

10,000,000 existing record writes

10,000,000 x 4 (1 WCU is 1KB) = 40,000,000 WCU

Total Cost: $50

Combined cost across all services < $150

The cheapest, non-t-series, multi-az, Postgres RDS is over $200/month and can’t come close to the availability and scalable performance of DynamoDB.

Final Thoughts I’ll leave you to figuring out how to write the code that uses the new table. I do recommend starting by updating all the code that does a read and pointing them at the new table. If you are doing anything where you use a consistent read after a write you’ll need to pay special attention to this code, and move both the read and write at the same time. Once everything is reading from the new table you can start to update any remaining code that is writing to the old table, and have it start writing to the new.

Hopefully you’ve learned that, while you don’t want to change your access patterns often, when you need to make a change there is a way forward without downtime and limited effort. Now you have one less argument against DynamoDB.