In my previous post I talked about why you need to think about data and security differently when working on a multi-tenant application. In this post I’ll dig in a bit deeper and show you what we did at ByteChek (RIP) for our multi-tenant strategy.

The Architecture

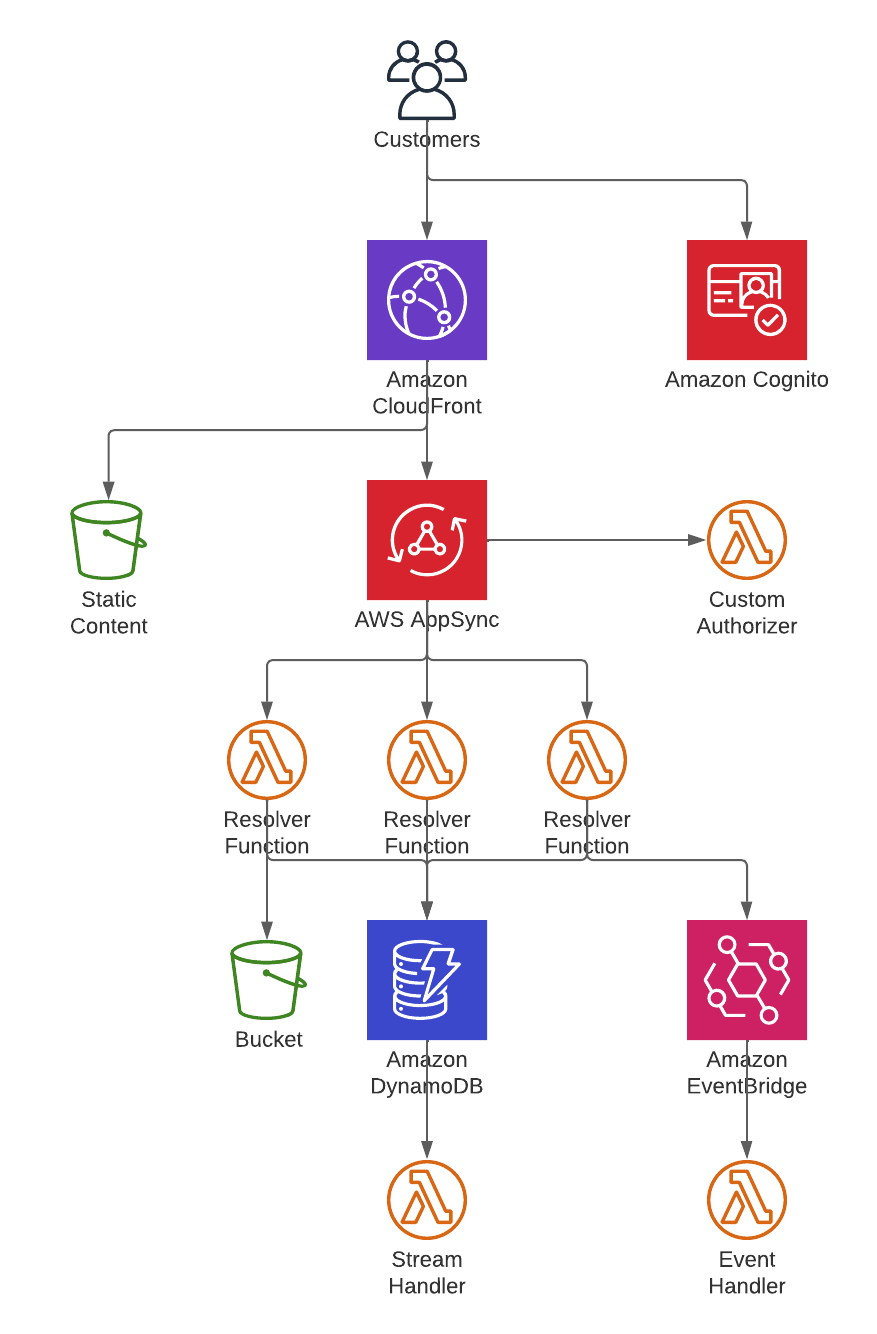

To start, let’s talk a bit about the high level architecture of the platform. 100% of the ByteChek platform is serverless. We use services like AppSync and API Gateway for synchronous communication and EventBridge, SNS, and SQS for asynchronous communication. Data is stored in S3 and DynamoDB. Compute is Lambda with a sprinkle of Step Functions for some coordination within a service. Like I said, 100% serverless. Here is a simple version of what it looks like:

Custom Authorizer

Our user interface is a React app. We use Cognito for user authentication and pass in a JWT to AppSync for requests from the app. This is the beginning of the multi-tenant strategy. As a request comes in to AppSync we use a custom authorizer on the request. There are a lot of things you can do with a custom authorizer, but the important piece for this conversation is called the resolver context (resolverContext in the JSON). This is a place where you can add anything you want to the request payload that AppSync will send to its resolvers. We use the resolver context to store credentials for the tenant of the user.

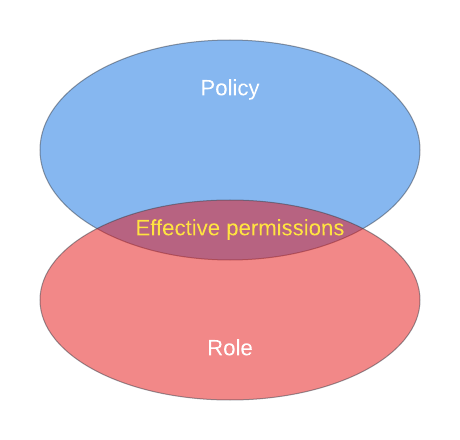

Where do we get these credentials? We use the STS (security token service) in AWS to request credentials. One of the features of the STS assume role API is the ability to pass in a policy with the request. This policy is combined with the policy of the role and the result is a set of permissions that are limited to the union of the two policies. Included in the request from Cognito is the tenant ID of that user. We use that ID to create a policy that limits access to just that tenant’s resources. We then pass those credentials along with the request, in the resolver context. I’ll show you what that looks like a bit later.

Using the Credentials

As I mentioned, we use Lambda for our compute, so all of our AppSync resolvers are Lambda functions. I’d love to do some direct integrations here (like read/write directly from/to DynamoDB) but we need some support from AWS on this front. A recent addition to Step Functions to support assuming a role within a task is step in the right direction, so I feel pretty confident that the future is bright for these options. Anyway, back to our solution. Typically when you create a Lambda function you assign it permissions to do whatever it is that the function needs to do. This will include things like writing to CloudWatch Logs, possibly X-Ray, as well as making calls to a DynamoDB table or S3 bucket. In our platform these functions are almost never granted permissions for the latter. Permissions to read or write to DynamoDB and/or S3 are instead granted via the credentials passed in via the resolver context. This means that the function itself cannot make a call to get or update data directly. From a security perspective that has removed the possibility of a developer accidentally writing code to do so. Instead we provide code for them to call that takes in the AppSync event and returns an AwsCredentialIdentity (JavaScript SDK v3) object that can be use with a DynamoDB or S3 client (or any other AWS client). For a developer this isn’t much different than what they might be already used to doing. The biggest difference is that the client has to be created within the context of the request instead of being shared. If a developer forgets to pass in the credentials the calls don’t work because the default credentials don’t have the necessary permissions.

Asynchronous Activity

As you’ve likely noticed, everything up to this point has been for a synchronous request made from AppSync. You likely also recall that we used services like EventBridge for asynchronous operations. How does this all work for asynchronous code? Most asynchronous actions are a result of a synchronous request, and so you might be tempted to think you can just pass along the credentials from the synchronous request and all is well. Not so fast. First, those credentials have a time limit. The default and max is one hour. While an hour is surely good enough for most things you want to be careful not to find yourself in a situation where a failure leads to an extremely difficult recovery. Also, keep in mind that a request may start near the end of that one hour limit, meaning you may be left with far less. Second, not all paths provide a way to do this neatly (DynamoDB streams come to mind here). You certainly don’t want to be storing credentials. And finally, let’s not forget I said “most”, which means there are things that don’t have any context to pull from. Any scheduled operation would fall into this category.

For asynchronous code our Lambda functions follow the same rule as our synchronous code; no permissions to access DynamoDB or S3. Instead they are granted permission to get credentials for a tenant. These credentials are the same credentials that are used for the synchronous case, they just are requested instead of being passed in. Everything in the system has a tenant ID in it – whether it’s a record in a DynamoDB table, or a message sent in EventBridge. As we process a record we use the tenant ID to request the credentials and use those credentials to get a DynamoDB or S3 client. Once again, if a developer forgets to pass in the credentials the calls don’t work. Furthermore, if we somehow have the wrong credentials it won’t work either.

A side note here. You may be asking why we don’t just request the credentials in the synchronous case. While there are some potential advantages to that approach, not the least of which is consistency throughout the code base, there is a reason to not. For synchronous request any time added to the processing of a request degrades the user experience. By getting the credentials during the custom authorizer we greatly reduce how often we need to get these credentials. You can control the cache timeout on the authorizer (we have it set to 15 minutes). This means that you only request the credentials once during that time. That can be a significant reduction in STS calls.

The Credentials

Okay, we’ve seen a lot about the flow of the system and when and how we get credentials. Let’s take a little bit of time to look at the specifics of the policies. I’m going to be broader in my policies that you might want to actually be, but you should be able to get the idea here.

First, let’s take a look at the policy attached to the role that we will be assuming. It looks something like this:

{

"Version": "2012-10-17",

"Statement": [

{

"Action": [

"dynamodb:*Item",

"dynamodb:Query"

],

"Resource": "*",

"Effect": "Allow"

},

{

"Condition": {

"StringEquals": {

"s3:prefix": [

""

],

"s3:delimiter": [

"/"

]

}

},

"Action": "s3:ListBucket",

"Resource": "arn:aws:s3:::*",

"Effect": "Allow"

},

{

"Action": [

"s3:ListBucket",

"s3:ListBucketVersions"

],

"Resource": "arn:aws:s3:::*",

"Effect": "Allow"

},

{

"Action": [

"s3:PutObject*",

"s3:GetObject*",

"s3:DeleteObject*"

],

"Resource": "arn:aws:s3:::*",

"Effect": "Allow"

},

{

"Action": "cognito-idp:*",

"Resource": "*",

"Effect": "Allow"

}

]

}

Notice that this policy grants some pretty broad permissions, and it needs to. This role will be used for all requests to customer data within the system. The key is the policy used when assuming the role. That policy looks something like this:

{

"Version": "2012-10-17",

"Statement": [

{

"Action": [

"dynamodb:*"

],

"Effect": "Allow",

"Resource": [

"*"

],

"Condition": {

"ForAllValues:StringLike": {

"dynamodb:LeadingKeys": [

"TENANT_1_ID*"

]

}

}

},

{

"Action": [

"s3:ListBucket"

],

"Effect": "Allow",

"Resource": [

"arn:aws:s3:::*"

],

"Condition": {

"StringEquals": {

"s3:prefix": [

""

],

"s3:delimiter": [

"/"

]

}

}

},

{

"Action": [

"s3:ListBucket",

"s3:ListBucketVersions"

],

"Effect": "Allow",

"Resource": [

"arn:aws:s3: : :*"

],

"Condition": {

"StringLike": {

"s3:prefix": [

"TENANT_1_ID/*"

]

}

}

},

{

"Action": [

"s3:*Object*"

],

"Effect": "Allow",

"Resource": [

"arn:aws:s3:::*/TENANT_1_ID/*"

]

}

]

}

Notice the conditions and resources that include TENANT_1_ID in them. It’s those parts of this policy that limit the access to just that tenant’s data.

As I mentioned earlier, the effective permissions when assuming a role are the union between the role’s policy and the policy of the assume role request. This means that even if I add something to the policy when assuming a role I won’t actually have that permission. Or if I include a permission in the role but don’t in the policy of the request.

By making tenant data security a foundation of the system we’ve made it really easy for developers to do the right thing while making it really hard not to. Starting your multi-tenant SaaS application off with a good foundation will save you from potential headaches in the future.